- Jan 9, 2026

When Yoga Hurts: The Hidden Risk for People With Spinal Osteoporosis

- Marta Shedletsky

- 0 comments

Why some poses can damage fragile bones — and how yoga can be practiced safely to support bone health

Yoga is widely seen as gentle, healing, and safe, and for many people, it truly is. Doctors often recommend yoga for back pain, joint pain, stress, anxiety, and overall well-being. Many of those doctors may never have stepped onto a yoga mat themselves, but they know yoga has a long-standing reputation for helping people feel better.

And they are not wrong.

Yoga is for everyone.

But not every yoga posture is right for every body.

Asana, the physical posture practice of yoga, is a form of physical exercise. It offers much more than fitness alone, including breath awareness, nervous system support, and a deeper connection between body and mind. But, like any physical activity, yoga can help or hurt, depending on how it is practiced and by whom.

When osteoporosis, especially spinal osteoporosis affecting the vertebrae, is part of the picture, some yoga postures, fitness exercises, and even everyday movements can place too much stress on fragile bones. This often surprises people, especially those who have practiced yoga, Pilates, or group exercise classes for years and have always felt better moving their bodies.

It is easy to assume that if something feels good, is widely recommended, and is considered gentle, it must be safe. But yoga is not a one-size-fits-all practice. Some postures can support bone health, while others can quietly cause harm when bone density is low.

Understanding what helps and what can hurt is not about fear.

It is about practicing yoga with awareness, common sense, and respect for the body you have today.

Osteoporosis Is Common and Often Silent

Osteoporosis affects millions of people, and it most often begins around menopause and perimenopause, the time leading up to the last menstrual period and the years immediately following it. Hormonal changes during this transition play a major role in bone loss, which is why women are affected far more frequently than men, although men are affected as well, often later in life.

According to the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation, one in two women over the age of 50 will experience an osteoporosis-related fracture in her lifetime. Many of these fractures involve the spine.

What is less widely known is that spinal fractures are often silent. There may be no sharp pain, no fall, and no obvious injury. Instead, fractures can develop gradually, through repeated stress on bones that have quietly become weaker.

Many women in their 60s, 70s, and 80s who have osteoporosis do not realize it, often because they feel no pain and have never broken a bone.

I frequently hear from women who say they felt fine, stayed active, and had no reason to suspect a problem. Some only discovered low bone density after attending a workshop or class and deciding to get a DEXA scan out of curiosity. Many are genuinely surprised by the results.

Osteoporosis does not require a dramatic break to be present. Bone density can decline slowly over time, especially if it has not been checked in 5, 10, or even 20 years. Small, repeated stresses can lead to microfractures that go unnoticed when they occur.

Over time, these changes may show up as:

Loss of height

A rounded or stooped upper back

Ongoing back discomfort or fatigue

Reduced balance and confidence

A higher risk of future fractures

Because osteoporosis often progresses quietly, awareness and early education are essential. At the same time, this does not mean giving up movement or yoga. Yoga, when practiced in a very specific and informed way, can help prevent further bone loss, strengthen bones, and support better posture and balance. The key is learning how to use the practice for benefit rather than harm, and understanding which movements support bone health and which ones need to be modified or avoided.

Why the Spine Is Especially Vulnerable

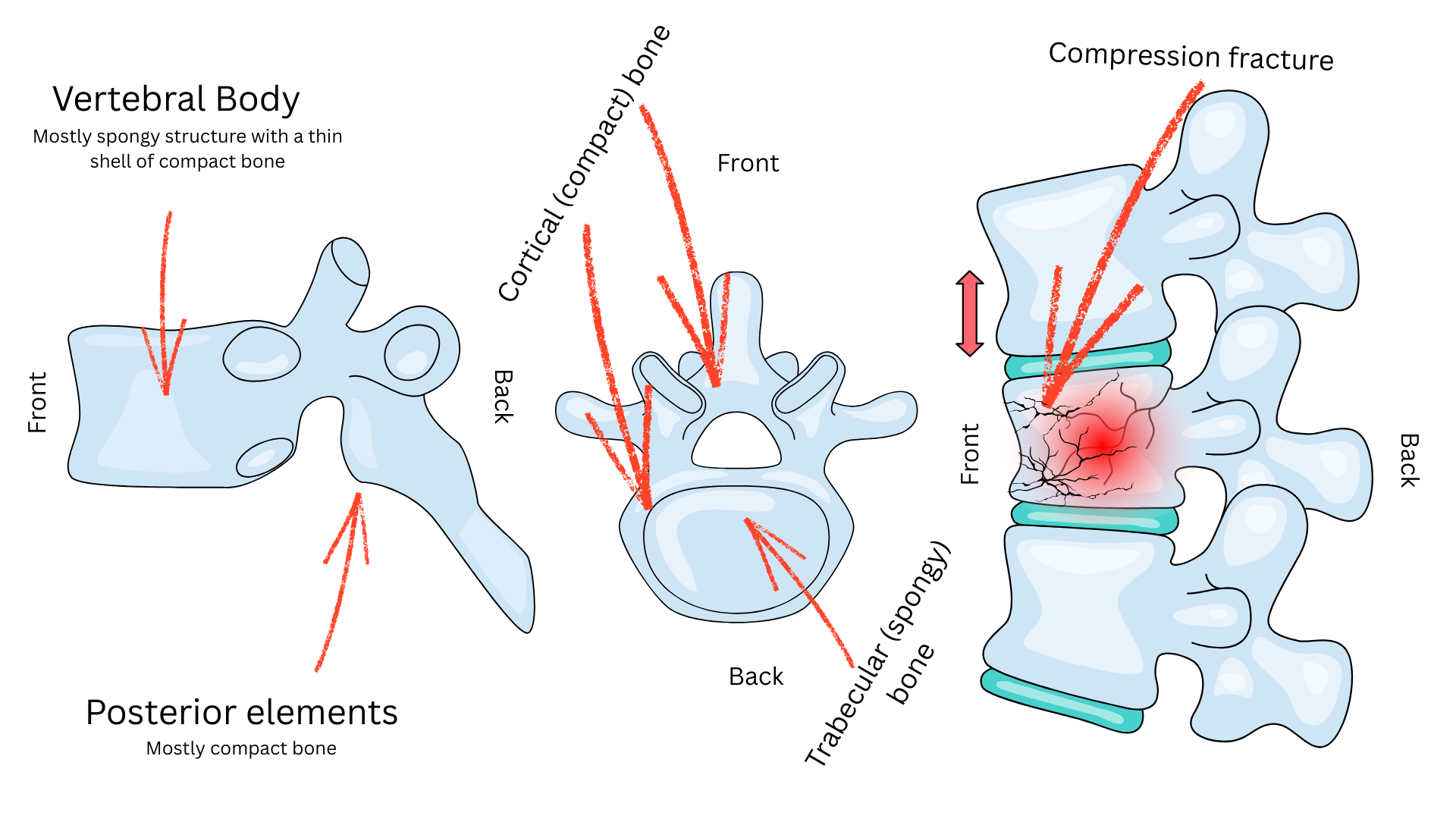

To understand why certain yoga poses and everyday movements can be risky, it helps to understand how the vertebrae are built.

A vertebra is not a solid, uniform block of bone. The front and back of each vertebra are structurally different and serve very different purposes.

The front portion of the vertebra, called the vertebral body, is the main weight-bearing structure of the spine. It is designed to support the body's weight in standing, sitting, and during movement. This part of the vertebra is made largely of trabecular, or spongy, bone, with only a thin outer shell of harder bone.

Trabecular bone is highly metabolically active, making it the first type of bone to lose density with aging, menopause, and osteoporosis. As bone density decreases, this front portion of the vertebra becomes more vulnerable to compression. This is why most osteoporotic spinal fractures occur in the vertebral body, often collapsing slightly in the front and creating a wedge shape.

The back portion of the vertebra is built differently. It is made of denser bone and forms the structures responsible for stability, muscle attachment, and movement control. These posterior elements guide how the spine moves and help support posture, but they are not designed to bear the body’s weight in the same way the vertebral body does.

Because of this structural difference, where force travels through the spine matters greatly. Movements that repeatedly load the front of the vertebra place stress on the area that is already most vulnerable in osteoporosis, while movements that support upright posture and balanced muscle engagement can help protect the spine.

Understanding this basic anatomy helps explain why certain movements may quietly cause damage, and why others, when practiced correctly, can support spinal health and bone strength.

What Happens in a Forward Bend

When the spine flexes, rounding forward in movements like forward folds, cat pose, roll-downs, crunches, or bending to pick something up, body weight shifts toward the front of the vertebra.

This creates:

Increased compression exactly where the bone is weakest

A wedging force on the vulnerable front of the vertebral body

Repeated stress that osteoporotic bone may not tolerate

In healthy bone, this load may be managed.

In osteoporotic bone, even everyday forward bending can lead to microfractures.

Because these fractures often happen gradually, people usually do not feel them in real time. The damage accumulates quietly, and the effects may only become noticeable later.

This is also what makes forward bends confusing. They often feel good. Stretching can release endorphins, calm the nervous system, and reduce muscle tension. Many people leave a yoga class feeling relaxed, open, and relieved, with the familiar sense of “I feel great after yoga.”

But muscle relief and nervous system calming do not reflect what is happening inside fragile bones.

So the question becomes: is that temporary feeling worth the long-term risk to the spine?

It is also important to remember that risk does not come only from yoga classes or workouts. Daily life matters just as much. For people with fragile bones, repeated spinal flexion shows up in ordinary activities such as:

Picking up heavier objects from the floor

Tying shoes with a rounded back

Getting on or off the floor without support

Curling up to get out of bed

When bone density is low, body weight alone can be enough to cause damage if movement patterns are not adapted.

The good news is that there are many ways to move that protect the spine while still allowing people to stay active, independent, and confident. There are yoga postures that can create the same sense of well-being while also supporting bone health, and practical strategies for everyday movements so that tasks like bending, lifting, and getting up or down can be done in a safer, more informed way.

You do not lose the benefits of yoga or daily movement when forward bends are limited or avoided.

The practice — and life — become more precise, more intentional, and far more supportive of long-term bone strength.

Feeling good in the moment does not always mean a movement is safe for fragile bones.

Why Backbends Are Different — and Often Helpful

Spinal extension, often referred to as backbending, affects the spine in a very different way than forward bending.

When the spine lengthens and extends with control:

The load is redistributed away from the fragile front of the vertebra

Forces are directed more evenly through the spinal structures

Postural and spinal support muscles engage strongly

The spine resists collapse rather than folding forward

Because of these mechanics, spinal extension can be supportive and protective for people with osteoporosis when it is practiced correctly.

This does not mean collapsing into passive backbends or simply “being gentle.” In fact, for bone health, spinal extension often needs to be clear, intentional, and sometimes quite demanding, especially when there are no other underlying conditions limiting intensity or particular movements.

What matters is not softness, but precision and direction of force.

In a bone-focused practice, spinal extension emphasizes:

Controlled, purposeful effort, rather than quick or repetitive movement

Length with engagement, not compression

Stability and strength, not passive flexibility

Muscular work that creates a steady load, particularly in the postural muscles supporting the spine

When practiced this way, spinal extension provides meaningful mechanical stimulus to the bones while keeping the spine aligned and protected. It allows yoga to be both challenging and safe, and it supports the kind of consistent loading that bones respond to over time.

This is where yoga for bone health differs from general “feel-good” stretching. The practice may look simple, but it can be physically intense, focused, and deeply strengthening, while still respecting the realities of osteoporosis.

The Good News: Yoga Can Strengthen Bones When Done Correctly

Here is the part many people do not hear often enough: osteoporosis is not a passive or hopeless condition.

Bones are living tissue. They respond to mechanical stress by adapting and becoming stronger, a principle supported by decades of bone science. This understanding forms the foundation of research-informed approaches to yoga for osteoporosis, including the work developed by Dr. Loren Fishman and others.

Specific yoga postures, and just as importantly, the way you practice them, can help:

Prevent further bone loss

Slow or stop the progression of osteoporosis

And in many cases, it improves bone mineral density when practiced consistently over time

In a community study of more than 700 participants with low bone density, a short daily yoga program was associated with significant increases in spinal and hip bone mineral density after years of regular practice, with no serious injuries reported.

Other smaller controlled studies have shown that integrative yoga programs practiced several times a week over several months can lead to significant improvements in lumbar spine DEXA T scores in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Yoga works in part because it directs mechanical stress to the skeleton through muscular engagement, weight-bearing, and controlled spinal extension. When practiced with attention to alignment and loading patterns, yoga can target bones throughout the body rather than just one region, and it can be adapted to many ages, fitness levels, and stages of osteoporosis.

Importantly, this approach can be adapted to a wide range of abilities and stages of bone loss. For some people, it may look like a more supported practice using props and a slower progression. For others with strength and good mobility, it may be physically demanding while remaining safe.

What all effective practices share is consistency, intelligent loading, and commitment. Bones change slowly, and they respond best to repeated, intentional, and well-directed forces rather than random or passive movement.

Yoga does not need to disappear after an osteoporosis diagnosis.

It simply needs to be practiced with knowledge, precision, and purpose.

When practiced this way, yoga can be both a safe practice and a powerful part of a long-term bone health strategy, supporting strength, confidence, and resilience over time.

If You Want to Learn How to Practice Safely and Effectively

Yoga can support bone health at any age and at any stage of osteoporosis, but it works best when practiced with clear guidance and intention.

The approach to yoga for osteoporosis developed by Loren Fishman, and supported by clinical research, offers a structured and effective way to apply yoga principles specifically for bone health. This method is not about pushing limits or performing advanced poses. It is about learning how to place the body under the right kind of load, in the right way, so bones are supported, stimulated, and protected over time.

If you would like individualized guidance, private sessions are often the best place to start. I work with clients in person and on Zoom, tailoring the practice to your bone density, movement history, and overall health, and helping you build confidence in both yoga and everyday movement.

For those who prefer to learn independently or want to build a consistent home practice, I also offer a self-paced online course that teaches the principles, postures, and modifications step by step, so you can integrate them into your routine at your own pace.

If you would like to explore the research and methodology in more depth, I also recommend Yoga for Osteoporosis by Dr. Loren Fishman, which explains the science, the postures, and the long-term potential of yoga as a tool for bone health.

Osteoporosis does not mean giving up movement or resigning yourself to fragility. With the right education and consistent practice, yoga can become a powerful ally in maintaining strength, confidence, and independence for years to come.